Biodiversity and nation

My research focuses on the digital archival representation of animal species that Latin American countries consider their national symbols, with a focus on the decolonization of online collections of biodiversity through the analysis of text-based and visual materials. I am currently analyzing a selection of seventeen species of mammals and birds to critique literary and natural history constructions of nonhuman species in digital environments. This exploration also illuminates the strengths and limitations of biodiversity imaginaries and their impact on the digital representation of diverse communities in the Global South, especially racialized and Indigenous groups. With this project, I challenge conventional notions of “the national” in digital biodiversity heritage, imaginaries, and discourse. With a focus on materials available through the Biodiversity Heritage Library (BHL), I collect, visualize, and map data about these national species to contrast the national value held by biodiversity—as well as the knowledge production about these species available through BHL—with the actual geographical location of nonhuman species beyond national boundaries. My project thus constitutes a decolonial critique of digital and non-digital epistemic and archival constructions of biodiversity and nation.

Doctoral research

My doctoral research forms the basis of my postdoctoral project. My dissertation, “Virtual Biodiversities and Digital Knowledges: Latin American Biodiversities in and through the Biodiversity Heritage Library,” comprises a decolonizing study of BHL’s materials, catalog, and social media content to understand epistemic and visual constructions of biodiversity through digital artifacts.

Access my doctoral dissertation through McGill University

Sample case study: Panama

To understand the nuances of the representation of Panama and her biodiversity in BHL, we have to begin much earlier than BHL, with the history of the Panama Canal. The Panama Canal began as a French project in the late 19th century. However, after the separatist movement in Colombia, this region was ceded to the United States, which began the construction of the Canal in 1904 and concluded it in 1914. US control of the Canal continued until 1979 when it was transferred to the Panama Canal Commission, a joint agency of the US and Panama; and it was not until 1999 that the Canal’s administration was left exclusively in the hands of Panama. To understand how this context impacts the collections of BHL, I extracted the metadata of all materials in BHL that included the subject Panama in their subject lists.

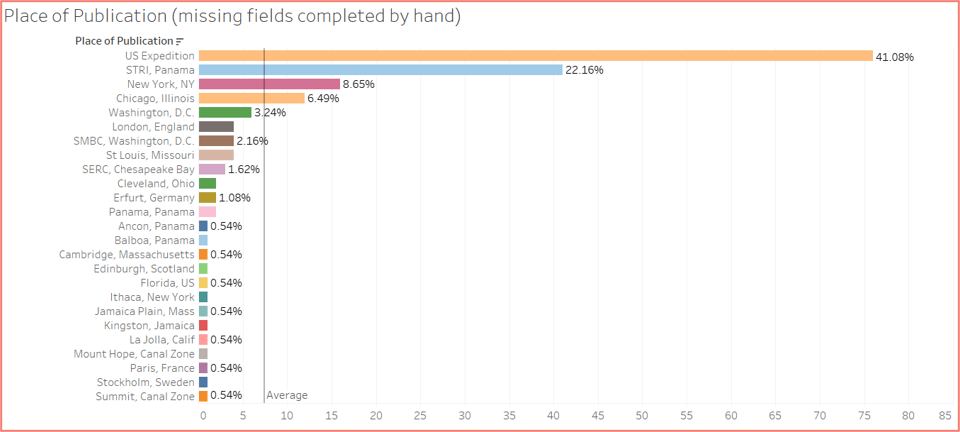

As shown on the previous graph, the initial metadata extracted from BHL showed that almost 70% of these 185 materials did not indicate a place of publication. After looking more closely at these records and manually filling in the blank categories, I found that most of the incomplete records were field notes, which explains why no place of publication was listed, given that field notes are not publications per se. However, upon closer examination, I found out that almost all field notes in the subset were the result of US-based expeditions to Panama, often organized by US government organisms and research institutions. To better grasp the impact of these affiliations on publication patterns of materials about Panama in BHL, I labeled their place of publication as “US Expedition.” As shown in the updated graph below, these materials make up 41.08% of this subset, meaning that US historical geopolitical interests in Panama greatly determine the knowledge production about Panama in BHL. Moreover, the ambiguities of the metadata of these records evidence the (neo)imperial nature of the archive, in that it conceals the power dynamics that occur in the production of these materials. Labeling these records as having no place of publication erases the dominance of the US in representing—or inventing, in José Rabasa’s words—Panama, demonstrating, at the same time, the gaps, shortcomings, and inherent biases of metadata fields.

Similarly, US-centrism manifests in the year of publication of materials about Panama, especially when we go back to the history of the US construction and administration of the Panama Canal throughout the 20th century. As shown on the chronological graph below, 87% of these records were published between the years 1903 and 1996, that is, during the US administration of the Panama Canal, with the peak occurring in the late fifties. Furthermore, almost all materials resulting from US-based expeditions were published between 1910 and 1983, meaning that 97.4% of these expeditions occurred during US control of the Panama Canal.

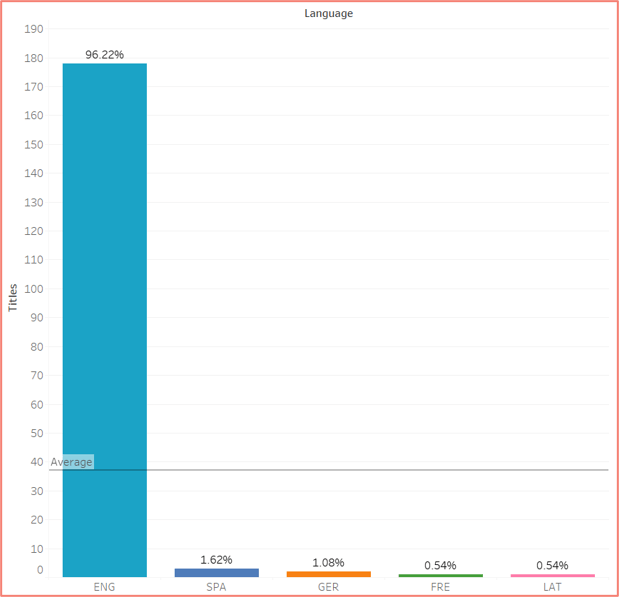

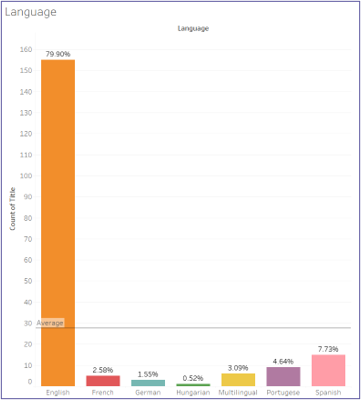

Finally, to add yet another layer to the coloniality of BHL’s representation of Panama, it is fundamental to consider that only 3.78% of records about Panama are in languages other than English, and Spanish makes up only 1.62% of the subset despite 91.9% of the total population of Panama in 2022 being native speakers of Spanish according to Instituto Cervantes.

Finally, to add yet another layer to the coloniality of BHL’s representation of Panama, it is fundamental to consider that only 3.78% of records about Panama are in languages other than English, as shown in the graph to the right.

Spanish, in contrast, makes up only 1.62% of the subset despite 91.9% of the total population of Panama in 2022 being native speakers of Spanish according to Instituto Cervantes.

Given these patterns of publication across time—alongside the importance of US expeditions in the production of the knowledge contained in BHL—it is possible to conclude that biodiversity-related epistemologies about Panama in the Library are greatly subsumed to US history, politics, and economic interests. While the mission of BHL is to provide access to global knowledge about biodiversity heritage, the narratives it perpetuates through its collection and its metadata are still deeply rooted in geopolitical and colonial dynamics, which will unavoidably transfer into any knowledge production stemming from BHL’s materials. The (hi)stories of the biodiversity of Panama that BHL tells are not those of Panama but those of Panama through the (neo)imperial epistemic lenses of the United States. BHL does not narrate the biodiversity heritage of Panama—and Panama herself—from a neutral standpoint but from a Global-North-centric, US-centric, and Anglocentric stance.

Another key issue in the case of BHL relates to the intraspecies relationships that it enables and prevents. To better grasp what this means, I focus on the case of the national bird of Panama, Harpia harpyja, also known as harpy eagle or águila harpía in Spanish. Harpia harpyja was first introduced to Western taxonomic systems by Carl Linnaeus in 1758 under the taxon Vultur harpyja. This species, which is classified at the greatest threat of becoming endangered according to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, can be found in Mexico and Central and South America. The largest population of Harpia harpyja in Central America though is located, in fact, in Panama, where it is protected by local laws, NGOs, and other organisms. It is, nonetheless, a key and protected species in multiple Latin American countries such as Mexico, Brazil, Ecuador, Nicaragua, Peru, and Paraguay. Many of these efforts are anchored in the cultural importance of Harpia harpyja for Latin American and Indigenous nations.

This species was established as the National Bird of Panama on April 10, 2002. Following this proclamation, April 10 was chosen as the Día Nacional del Águila Harpía in Panama, and the species was incorporated into the country’s National Coat of Arms. In the case of Indigenous cultures, Harpia harpyja has been a symbol of tribal chiefs in Amazonian cultures and an important motif in Chavín iconography in Peru, to give a couple of examples. Finally, Harpia harpyja participates as well in colonial (hi)stories as it exemplifies syncretism in Jesuit guaraní-Spanish dictionaries in Paraguay, where the association between Christ and another species, Aquila chrysaetos, was translated as japakani, the guaraní name for Harpia harpyja, to facilitate the conversion of Indigenous peoples to Christianity.

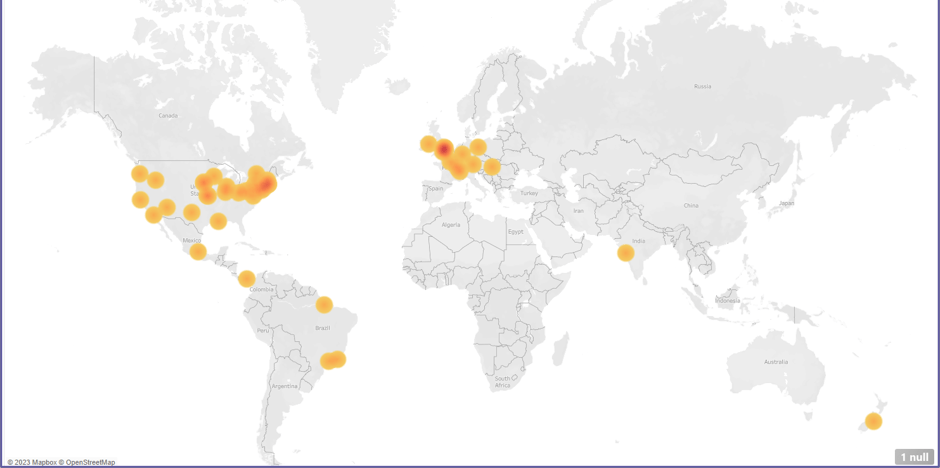

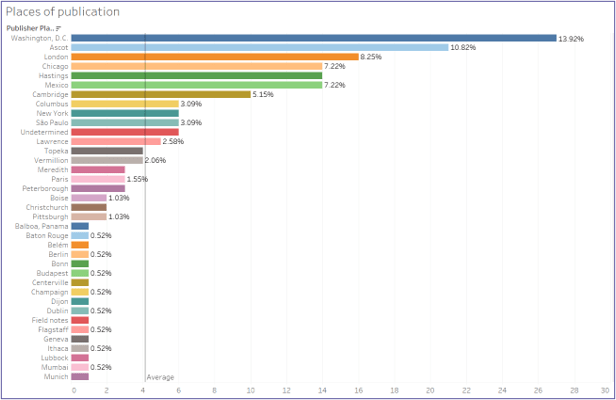

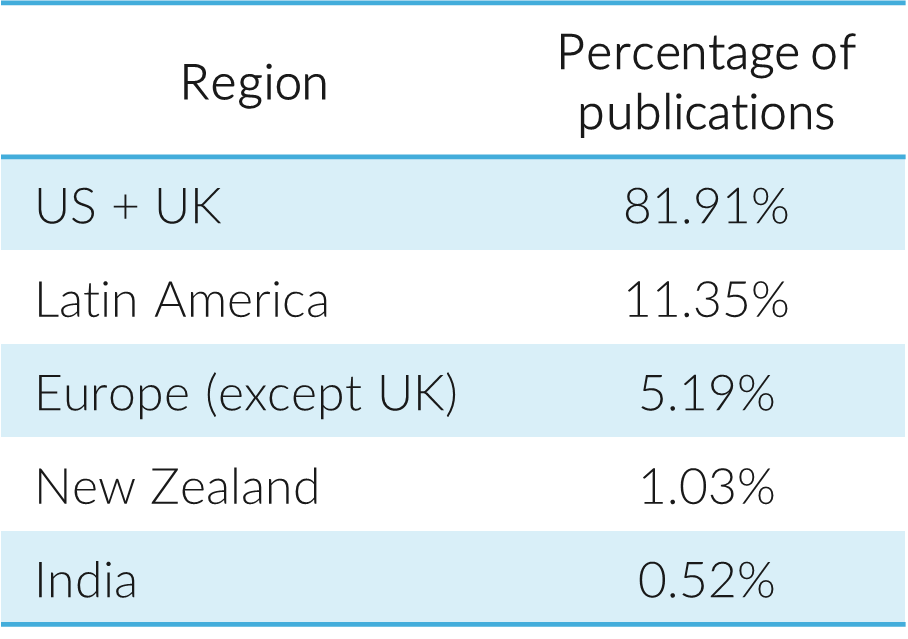

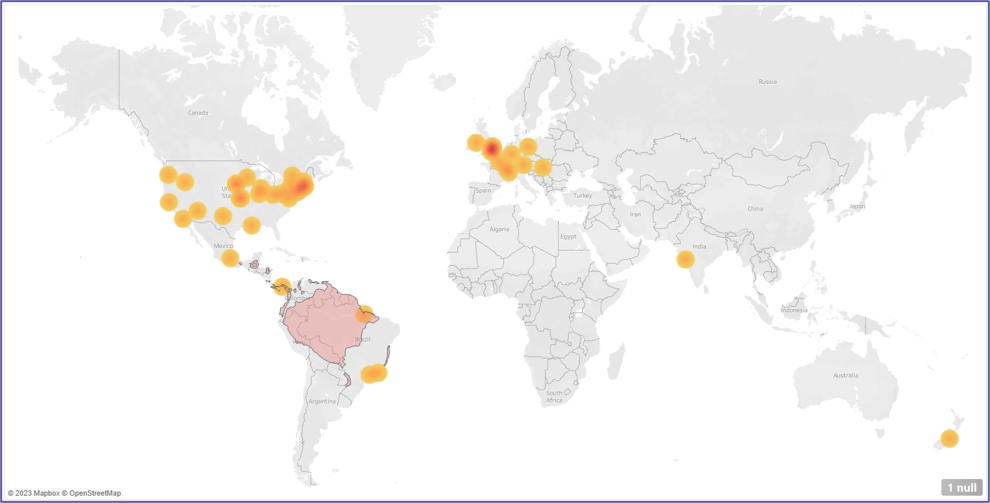

All things considered, then, it is easy to understand the multiple cultural and historical values that Harpia harpyja holds for Latin American and Indigenous nations, particularly, for Panama. How, then, are these values and shared bio-diverse (hi)stories represented in BHL? To explore this question, I downloaded the metadata of materials in BHL that mention the scientific name Harpia harpyja, using BHL’s built-in search by species. The map and graph below show the places of publication of the resulting 194 records, which are largely published in the US and the UK.

In simpler terms, what we see in this case is that 81.91% of materials about Harpia harpyja were published in cities across the US and the UK, with only 11.35% published in Latin American cities, of which only one title was published in Panama.

Below is a juxtaposition of the actual distribution of Harpia harpyja in the world according to IUCN Red List, showing its habitat as an endemic species of Latin America, and the map above (places of publication). Through this overlapping, we see a clear contrast between the knowledge production contained in BHL and the actual distribution of the species.

Despite the presence of Mexico, Brazil, and Panama as important sites of knowledge production in this subset, they are greatly overshadowed by publications from the Global North. Moreover, and similar to the case of materials about Panama, almost 80% of this subset is in English, with Spanish and Portuguese greatly underrepresented despite being the most spoken languages in the region where Harpia harpyja lives, not to mention the complete absence of Indigenous languages.

Graph generated on Tableau with data from BHL as of October 2022

Putting together the cases of Panama and her national bird, Harpia harpyja, I conclude that, despite its global outlook and the value of open access, BHL continues to be ingrained in a long history of epistemic coloniality and violence towards human and nonhuman subjects. For BHL’s values of globality, community, collaboration, and accessibility to be fully attained, the Library must reassess its collections vis-á-vis Latin America, the Global South, Indigenous nations, and nonhuman species and (re)frame its archival practices in a decolonial light, for example, by diversifying global partnerships, expanding multilingual interfaces and collections, and establishing decolonial and contextualizing parameters for metadata. Only then will the knowledge BHL disseminates truly represent the commons of biodiversity heritage through equitable, sustainable, and fair bio-diverse (hi)stories.

Other research highlights

- Coordinator of the Environmental Justice Archive of Virginia (August 2022 – May 2024), William & Mary. In collaboration with Dr. Monica Seger and Dr. Alan Braddock. Planning, development, and organization of the newly created Environmental Justice Archive of Virginia (EJAV), including web presence, text, and design. Development of submission and selection guidelines and decolonial and equitable metadata standards.

- Project Manager of Digital Humanities Initiatives (January 2022 – June 2022), McGill University. Under the supervision of Graduate Program Director of Digital Humanities, Dr. Andrew Piper. Web content development, social media administration, communications, website development and maintenance.

- Translator (October 2021, February 2022 – May 2022, September 2022), Alliance of Digital Humanities Organizations (ADHO). Under the supervision of Dr. Cecily Raynor (McGill University) and Prof. Marie-France Guénette (Université Laval). Translation of ADHO’s official website from English to Spanish as part of the Organization’s Multilingual agenda. Translation of ADHO’s Call for Papers for the DH 2022 (October 2021) and DH 2023 (September 2022) conferences.

- Collections Analysis Intern (June 2021 – August 2021), Biodiversity Heritage Library. Under the supervision of BHL Program Director Martin Kalfatovic. Funded by the Graduate Internship Program, McGill University. Web analytic data and collection and text mining analyses of BHL’s online catalog and collections. Identification of un- and underrepresented sources and sensitive content. Consultant for equitable and decolonial representation practices and policy.